California’s mega-drought officially ended three years ago but may have turned the Creek Fire into a monster.

By killing millions of trees in the Sierra National Forest, the historic drought that ended in 2017 left an incendiary supply of dry fuel that appears to have intensified the fire that’s ravaged more than 140,000 acres in the southern Sierra Nevada, wildfire scientists and forestry experts said Tuesday.

“The energy produced off that is extraordinary,” said Scott Stephens, a wildfire scientist at UC Berkeley. “Large amounts of woody material burning simultaneously.”

What’s more, the Creek Fire is shaping up as a frightening template for other wildfires that could ignite in heavily forested areas that suffered extensive tree loss.

“This might provide this first glimpse into the future we’re in for,” said LeRoy Westerling, a climate and wildfire scientist at UC Merced.

This June 6, 2016, photo shows patches of dead and dying trees near Cressman, California. California’s drought and a bark beetle epidemic have caused the largest die-off of Sierra Nevada forests in modern history. Scott Smith ASSOCIATED PRESS

Brittany Covich of the Sierra Nevada Conservancy, a state agency that funds projects aimed at reducing wildfire risks in forests, said what’s happening in Fresno County could easily take place in the Tahoe National Forest and other areas with lots of dead trees.

“That’s the fear we have across the Sierra Nevada,” Covich said.

An estimated 140 million trees perished during the five-year drought, which was officially declared over in 2017 by former Gov. Jerry Brown. California and the U.S. government, which controls a majority of the forestland in the state, have barely begun the process of removing the carcasses, leaving fuel loads waiting to be ignited.

“The scale of the problem is enormous,” said Steve Lohr, acting deputy regional forester at the U.S. Forest Service. “We’re doing the best that we can. Is that good enough? Probably not.”

And nowhere is the problem more severe, it seems, than the Sierra National Forest.

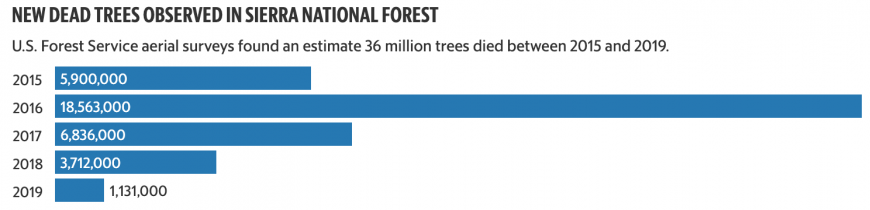

Over the last five years, a period extending beyond the end of the drought, the Sierra National Forest lost 36.1 million trees to drought, bark-beetle infestations and other woes. That’s more than any other national forest in California, and nearly a quarter of the total. The toll translates to about 26 trees killed per acre.

According to a Cal Fire summary, the bark beetle has killed at least 80 percent of the trees in the area of the Creek Fire.

“It’s ground zero for tree mortality,” Covich said. “Where the burned over the last couple of days are areas that had extreme tree mortality. Dozens of dead trees per acre is probably having a pretty significant impact.”

It isn’t as if the fire risk in the Creek Fire burn zone was a surprise to anyone. The area around Shaver Lake, where the fire has done some of its most severe damage, is a sea of red in Cal Fire’s risk map. That signifies it lies in a “very high fire hazard severity zone,” the agency’s designation for the areas considered most vulnerable to a major disaster.

‘EXTREME WEATHER AND FIRE BEHAVIOR’

While the cause of the Creek Fire remains under investigation, Stephens said there’s little doubt that climate change helped set the stage for the fire. Hot weather exacerbated the effects of the drought, drying out vegetation and leaving the forest vulnerable.

It’s the millions of dead trees, he said, that have made the Creek Fire such a remarkable event.

He said a wildfire generally burns hottest at its leading edge. Trees that were already dead tend to smolder — “like a burning cigarette,” the Berkeley scientist said — but don’t contribute much to the heat.

The Creek Fire is turning out differently. He said the heavy volume of dead trees — some lying on the ground, some still upright — is adding enormously to the overall fuel content, making the interior of the fire burn just as intensely as the edge.

“The large amount of dead and downed fuels ... create extreme weather and fire behavior,” he said. “The energy produced off that is extraordinary ... large amounts of woody material burning simultaneously.”

Among other things, the overly-hot interior contributes to the dramatic plumes of smoke shooting tens of thousands of feet into the air above the Creek Fire, he said. The plumes are worrisome because they when they collapse, they infuse the fire with massive blasts of air.

In addition, unusual nature of the Creek Fire, with extreme temperatures throughout the fire zone and not just on the front edge, means it’s hard to get a handle on where the fire will go next.

“When you have fire that runs 15 miles in one afternoon, there’s no model that can predict that,” said the Forest Service’s Lohr.

CALIFORNIA’S FOREST DEAL WITH TRUMP

Part of the trouble with forestland in California is there’s so much of it. Forestland, much of managed by the federal government, accounts for about 33 million acres of California, one-third of the state’s total landmass.

For decades forest managers had a singular goal: To put out fires as quickly as possible. This culture of “fire suppression” left the forests heavily overgrown and highly vulnerable to even bigger fires, many forestry experts believe.

That’s been changing in recent decades, as federal and state officials try to “thin” out the forests by mechanically removing trees and brush, or engineering “prescribed burns” during winter months. Under Brown, for instance, the Legislature appropriated $1 billion over five years to reduce fuel loads.

Some environmentalists, though, say thinning the forests is a terrible mistake.

Ecologist Chad Hanson of the John Muir Project said some of the worst damage from the Creek Fire is in areas that were logged following earlier fires.

When dead trees are logged, grass, brush and other highly flammable material take their place, Hanson said. Leaving the dead trees in place, he said, can actually slow the spread of a fire.

“Forests with more dead trees do not burn more intensely,” Hanson said.

Nonetheless, there’s a growing consensus among forestry experts that reducing the number of trees can help tamp down the risks of major wildfires. The Forest Service, for example, treated 208,000 acres of land in California last year and another 149,000 acres so far this year.

With relatively little fanfare, Gov. Gavin Newsom’s administration signed a landmark agreement last month with President Donald Trump’s administration, a rare bit of agreement between two factions that are frequently fighting each other.

The memorandum of understanding commits the state and federal governments to reduce fire conditions on 1 million acres of forest and rangeland each year by 2025 — roughly doubling the current amount of treatments.

‘THIS IS GOING ... TO LAST A LONG, LONG TIME’

But even achieving that ambitious goal would still leave millions of acres vulnerable. And the massive tree death during the drought has made the problem all the more daunting.

Treating the forests has been “compounded by the number of acres that we had that underwent tree mortality,” said Tony Scardina, the agency’s deputy regional forester. Because of that, the Forest Service has to “catch up to reduce that fuel load,” he said.

In the Sierra Nevada, removing trees and shrubs is often a painstaking process that can involve years of planning, environmental reviews, and sometimes litigation from those who don’t want to see trees come down.

And sometimes the planners get overtaken by events.

Steve Wilensky, a Calaveras County farmer who runs CHIPS — a nonprofit that secures government grants to build fuel breaks and thin forests in parts of the Sierra Nevada, said he’s had two crews removing shrubs and grass from the Mariposa Grove of Giant Sequoias, an iconic stand of ancient trees in the southern end of Yosemite National Park.

One of the crews is from the Big Sandy Bandy of Western Mono Indians, who live on a rancheria near Auberry, about 40 miles south of the Mariposa grove. When the Creek Fire churned toward Auberry, the workers were evacuated along with other residents. Unfortunately, they had to leave their equipment behind.

“All their equipment, the saws, the chippers, the trucks, were left in harm’s way,” Wilensky said.

The other crew, though, is still on the job. With millions of acres of land needing treatment and wildfire risks seemingly growing every day, Wilensky said the work can’t wait.

“They lit out early this morning,” he said Tuesday. “They’re working 10- to 12-hour days,” he said. “This is going to be a state issue that’s going to last a long, long time.”