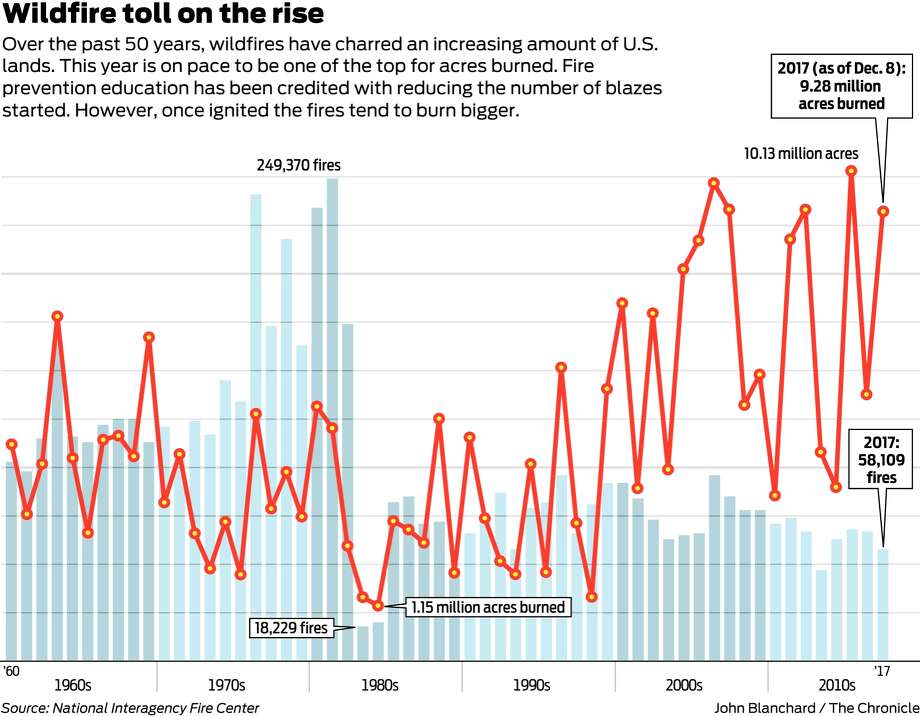

This year’s wildfire season, still on the move in Southern California, is one for the record books.

Federal firefighting costs soared to a new high. The nightmarish Wine Country blazes leveled more than 5,000 homes and killed 44 people. And two weeks before Christmas, when fire danger is typically gone, flames continue to eat through the outskirts of Los Angeles and San Diego, chasing tens of thousands from their homes and threatening the cushy estates of Elon Musk and Jennifer Aniston.

The challenge, the experts say, is doing enough to meet the mounting threats posed by a warming climate and the housing development that’s put more people in fire-prone places.

“All we can really do is make a difficult situation or a moderate situation better,” said Scott Stephens, a professor of fire science at UC Berkeley. “But I think we are beginning to see a change in our ability to deal with this. Even politicians are getting much more interested now.

“Not that they’re going to solve this,” he said, “but you have billions of dollars of losses and this type of havoc is becoming a big deal that has to be dealt with.”

Rising concern about California wildfires has translated into tens of millions of dollars for prevention and preparedness. Gov. Jerry Brown’s cap-and-trade program alone is expected to deliver a new $225 million chunk of funding for fire and forestry programs this budget year.

Much of the money will go to communities to take the most fundamental, yet often effective, precautionary fire measures, from bulldozing fuel breaks around neighborhoods to installing new weather radar and smoke-detection cameras, to improving escape routes in subdivisions.

“What about just knowing your neighbors a little better?” suggested Stephens, who said North Bay residents weren’t as prepared as they could have been when deadly blazes ripped through Sonoma, Napa and Mendocino counties in October. “Maybe you have a person with a wheelchair down the street who has no way of evacuating on their own.”

Stephens said Northern Californians should take a lesson from their counterparts to the south, where experience with fast-moving fires appears to have paid off this past week. More than 200,000 people safely fled more than a half dozen major fires that erupted between Santa Barbara and San Diego counties, including the massive Thomas Fire in Ventura County, even amid the same speedy inland winds that carried flames through Wine Country. One death was reported as of Friday.

On the state level, the Department of Forestry and Fire Protection is working to brace for a nastier future by expanding its sweeping fuel reduction efforts, both with heavy equipment and prescribed burns. The agency also is ramping up enforcement of defensible space rules and sending dozens of state fire experts into local communities to consult on safety.

“There really is a huge investment,” said Cal Fire spokesman Daniel Berlant. “It’s giving us an opportunity to really change the landscape amid the increase in the severity of wildfires.”

Still, only so much can be done, experts say. Millions of homes stand in areas the state considers at risk for fire, generally rural places or suburbs that push into California’s wildlands. No matter how much residents prepare their homes and communities, the conflagrations that have naturally burned hills and valleys for centuries remain on a collision course with development.

Despite warnings not to build, the lure of open space and million-dollar views — as well as the need to shelter a growing population — have typically prevailed. Even areas with a history of fire, including the northern and eastern edges of Santa Rosa that burned in the 1964 Hanley Fire before lighting up again Oct. 8, have been repeatedly built out.

One study by researchers at UC Berkeley and the George Washington University suggests that development pressures will result in 645,000 houses in California’s most hazardous “very-high” severity zone by 2050.

While new homes face more stringent safety rules, requiring fire-resilient roofs and air vents that block out dangerous embers like those that crossed Highway 101 and ignited home after home in Santa Rosa, the measures offer only limited protection, especially against the type of powerful firestorms seen recently.

Moreover, most of the homes in hazardous areas lack updated safety features because they were built before the new codes took effect in recent decades.

Some planning leaders have pushed for older homes to be subject to today’s building standards, or have gone as far as suggesting that new construction be completely barred in previously burned areas, like the hills in Santa Rosa. Such proposals, however, have gotten little political traction.

“If we really want to protect lives and property, we have to look at our communities and respond from this direction,” said Richard Halsey, founder of the California Chaparral Institute in Southern California, which advocates for fire-safe planning.

“People say that the winds were so strong in the fires in Sonoma and Napa that there was nothing that could have been done. But I would challenge that statement,” he said. “They shouldn’t have built in that fire-shed in the first place.”

More people living in wild areas also means more chance of a fire igniting. Nearly all fires in California’s coastal mountains, including Wine Country and Southern California, are started by humans. Only the Sierra Nevada commonly sees lightning-caused burns.

The changing climate is another complicating factor in dealing with the state’s wildfires. Warmer temperatures and more variable weather have made for drier conditions that persist longer, meaning a more intense, drawn-out fire season.

In addition, emerging research has suggested that global warming is making the storm-blocking masses of air over the North Pacific, which caused California’s recent drought, more common. A study released last week by researchers at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory linked the greater frequency of this drying atmospheric ridge to melting sea ice.

“We’re increasing the probability of missing that season-ending rain and having the fire season continue further into the fall,” said LeRoy Westerling, a climate scientist at UC Merced. “A place like Napa or Sonoma is looking more like San Diego, while Southern California is having a fire season that extends all the way toward winter.”

The Northern California blazes were followed by a series of fire-smothering storms, but a lack of precipitation in Southern California allowed last week’s fires to explode into infernos once reserved for much earlier in the year.

Los Angeles has seen less than a quarter inch of rain since spring, compared to its historical average for the period of roughly 2 inches. The vegetation is ripe for flames after the state’s record hot summer.

This year’s troubles only intensify a trend. Nine of California’s 20 largest recorded wildfires have occurred in the past decade. According to one study published by researchers at Columbia University, as much as half the land burned in California and across the West since the 1980s is probably the result of global warming.

This year, big blazes in California as well as in Montana and Oregon have prompted the U.S. Forest Service to spend more than $2 billion on fighting fires. Nationwide, the total acreage burned is on pace to be one of the highest in more than a half-century, with some 9 million acres charred.

Cal Fire has chalked up one of its most expensive years, too. About 1.1 million acres have burned in California, nearly double the five-year average.

“It’s not like this is going to be a one-off year either,” said Westerling. “The underlying conditions are changing and will continue to do so.”