The wildfire season that has leveled hundreds of homes, closed roads and parks, and sent hazy smoke into major cities across the West has become the most expensive in U.S. history, officials said Thursday, marking another chapter in a year of brutal extremes linked to climate change.

A menacing one-two punch of record rain last winter and record heat this summer, following a historic drought in several Western states, gave birth to a bumper crop of grass and brush that has since dried out and burned up.

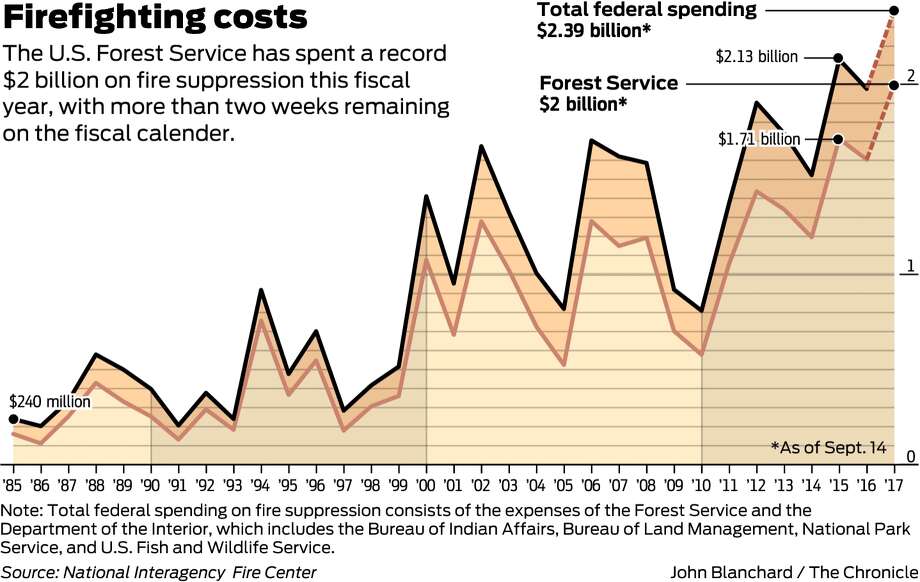

Big fires that have hit Montana, Oregon and California especially hard have thrust as many as 27,000 people to the fire lines, pushing the cost of fire suppression for the U.S. Forest Service to a milestone $2 billion this year, the agency reported.

The expense tops the agency’s previous record of $1.7 billion in 2015, with two weeks still remaining in the budget year, which runs Oct. 1 through Sept. 30. The cost does not include the smaller amounts spent by other federal and state firefighting agencies.

Forty-one large blazes burned out of control across the West on Thursday, the latest in a fire season that began early in California and is forecast to remain much livelier than normal through at least the end of the month.

More than 8 million acres have been blackened nationwide this year, an area larger than the state of Maryland. That’s nearly 50 percent more than what’s usually charred at this point in the year.

Montana has taken the brunt of the devastating season, with the picturesque Rocky Mountains turning into a tableau of flame and smoke. Blazes forced thousands from their homes and killed at least two firefighters.

In Oregon, the Eagle Creek Fire has lit up the scenic Columbia River Gorge while showering the Portland area with a steady supply of ash.

California has seen dozens of major fires, from the massive 96,000-acre Eclipse Fire in the Klamath National Forest near the Oregon border to smaller but more devastating blazes near Lake Oroville and Yosemite National Park.

“It started with several years of drought,” said Scott McLean, a spokesman for the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection, noting that a windfall of dead and dried-out trees set the stage for this year’s stark fire season. “They’re not coming back to life no matter how much rain you put on them.”

Instead, the wet winter created a buildup of grass that prompted several large fires in the state’s lower elevations in spring and early summer, only to be trailed by burns in the higher elevations as the year progressed, McLean said.

A record hot summer in California, which pushed the mercury to a chart-topping 106 degrees in San Francisco two weeks ago, only energized the fire season.

LeRoy Westerling, a climate scientist at UC Merced, said several factors play a role in increasingly severe fires across the West, including the nation’s history of fire suppression, which as a byproduct has left more fuel for fires to burn. Global warming is also in the mix.

“Higher temperatures mean more evaporation, which means drier fuels, and that means more fire,” Westerling said. “It’s complex, but climate change is really the back-seat driver, and it has been for decades.”